Chileno Valley Newt Brigade

– In the Press –

Index

2025

2024

KPIX | CBS NEWS BAY AREA, March 20, 2024 | The Newt Brigade, Marin County by Brian Hackney

Marin Independent Journal, March 15, 2024 | West Marin group acts as crossing guard to protect imperiled amphibian by Krissy Waite

2023

Point Reyes Light, June 7, 2023 | Newt brigade explores safe crossing by Ben Stocking

North Bay biz, April 26, 2023 | Caution: Newt X-ing by Bo Kearns

KRCB, February 14, 2023 | Newts find helping hands in their journey across the road by Noah Abrams

State of the Bay | KALW Public Media / 91.7 FM Bay Area, January 30, 2023 | Newt Brigade by Chris Nooney

KRON4 News, Bay Area, January 30, 2023 | Chileno Valley Newt Brigade is helping a local ‘jewel’ one newt at a time by Miabelle Salzano

The New York Times, January 24, 2023 | A ‘Big Night’ for Newts, and for a California Newt Brigade by Annie Roth

The Newt Normal, bioGraphic, 1-13-2023 | Story by Emily Sohn | Photographs by Anton Sorokin

Marin Conservation League Newsletter, Jan-Feb 2023 | STATUS UPDATE: Chileno Valley Newt Brigade — Protecting Rites (and Rights) of Passage by Kate Powers

2022

Argus-Courier, September 15, 2022 | Newt Brigade stands by as winter approaches by Lina Hoshino, Argus-Courier Columnist

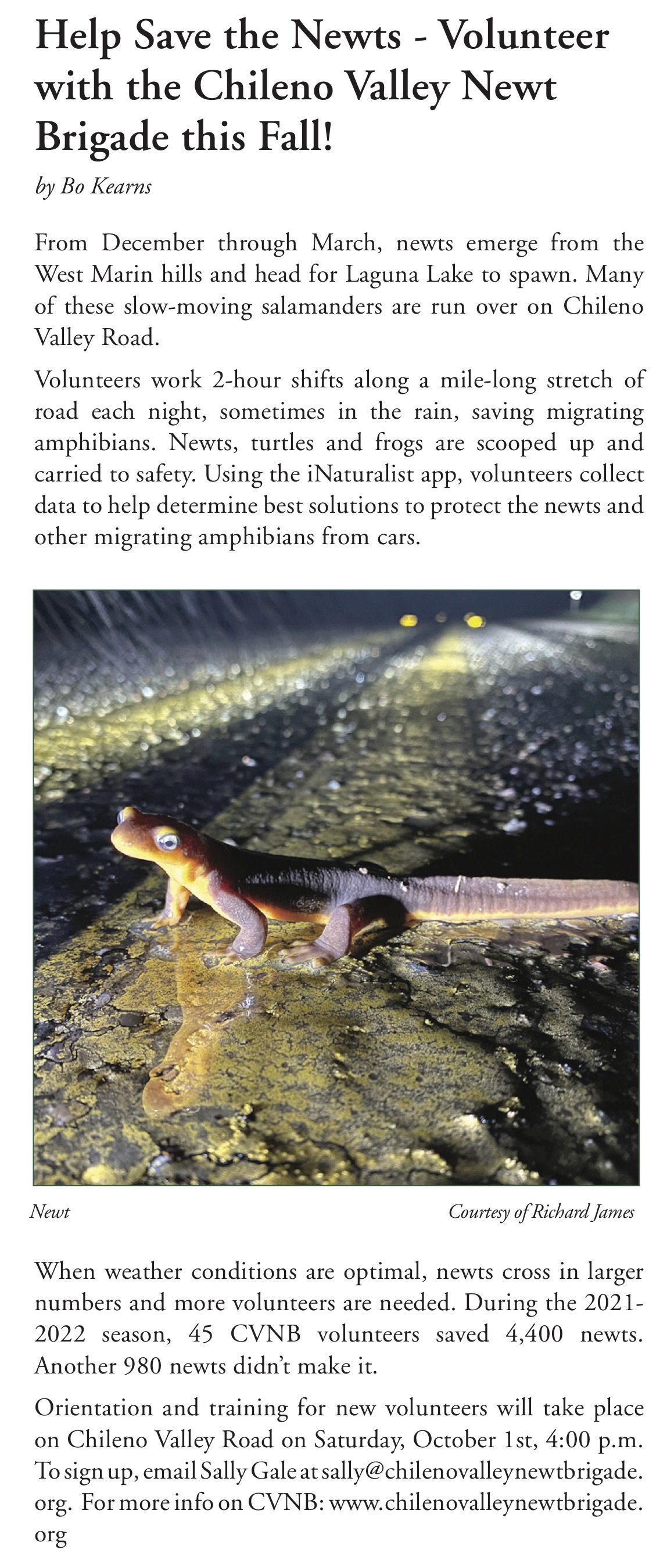

Madrone Audubon Society Newsletter, September, 2022 | Article by Chileno Valley Newt Brigidier Bo Kearns

WIRED, April 2, 2022 | How Does a Newt Cross the Road? With Lots of Human Help, by Maanvi Singh

The Guardian, March 27, 2022 | How does a newt cross the road? The teams trying to end a nightly carnage by Maanvi Singh

San Francisco Chronicle, March 22, 2022 | California highways are creating an extinction crisis. And mountain lions aren’t the only roadkill by Tiffany Yap

Podcast from Fifth & Mission, San Francisco Chronicle, March 4, 2022 | Newts Crossing: A Bay Area Biodiversity Crisis — Newt roadkill is a Bay Area biodiversity crisis

San Francisco Chronicle, Feb. 21, 2022 | Newts and roads don’t mix. So these Bay Area volunteers make sure they get to their destination, by Tara Duggan

Bay Nature, January 26, 2022 | “On the Road With the North Bay Newt Brigadiers” | Volunteers Save Thousands of Newts from Being Roadkill—But "We Can't Just Keep going Out there Every Year and Picking Up Newts for Three Months." by Emily Moskal

The Press Democrat, 1-13-2022 | Petaluma area volunteers group works to preserve native newt population

2021

Sonoma Magazine, March 2021 | Dream Drives: 3 Perfect Day Trips to Experience Spring in Sonoma County, by John Beck

2020

Marin Conservation League Newsletter, Nov-Dec 2020 | Nature Note Update by Bo Kearns

Newt Brigade | Nocturne Podcast | March 2020

| Hosted by Vanessa Lowe

Press Democrat | January 17, 2020

|

How to Spot North Bay Newts on the Move by Jeanne Wirka

2019

Point Reyes Light | December 4, 2019 | Newt brigade acts after rains by David Briggs

Point Reyes Light | July 31, 2019 Chileno Valley Brigade Will Ferry Newts This Winter by Braden Cartwright

KWMR Radio | Epicenter: West Marin Issues, October 15, 2025

Radio Interview with Richard James of the Chileno Valley Newt Brigade:

”News about newts! Richard James of the Chileno Valley Newt Brigade discusses their work.”

-

Jeff Manson: Well, if you've ever driven through Chileno Valley on a rainy night, you might have noticed some tiny, determined travelers crossing the road, California newts making their seasonal migration to breed. Unfortunately, that journey has become perilous, and a dedicated group of volunteers known as the Chileno Valley Newt Brigade has been working tirelessly to protect these vulnerable amphibians from road traffic and habitat loss, and joining us today is Richard James, one of the members of the brigade, to talk a little bit about the newt's remarkable migration, the community effort to save them, and what these small creatures can teach us about living in balance with the natural world. Hello, Richard, thanks for being here.

Richard: Oh, hi, Jeff. Thank you so much for having us out. It's, it's good to talk about it like you said. It's, it's the season.

Jeff Manson: It is the season. Yeah, those first rains, and here they come. For listeners who might not be familiar, let's just get the basics. What is the Chileno Valley Newt brigade? And how did that get started?

Richard: Well, it's a group of dedicated volunteers who are curious, who care about nature, and they care so much that they go out onto the road on very rainy and sometimes very cold nights, because that's when the newts move their migration. And we move them across the road. We actually take a we have everybody has a cell phone, a smartphone with the iNaturalist app on it, also known as iNat, and it's a citizen science tool for tracking all sorts of things, plants and animals. So we take a picture of every newt, and then we move it. We look at, okay, well, which way are you going? Let's get you across the road. And they they migrate in different directions, depending on if it's pre breeding season, like they're headed towards the Laguna. And then once they're done with that, then they move back. And then the year before is offspring that are now little. We've seen as small as, like, an inch and a quarter long, very, very tiny, up to maybe three inches. They are actually leaving the lake to go up into the hills, to go and enter a phase. I forget the technical term for it, but they rest up there. And so we move the newts both ways back to your original question of, how did it start? So there is a couple that lives out on Chileno Valley Road, Sally and Mike, Gale. And Sally's been out there. Her family's been out there since the 1800s in a really old farmhouse that they live on. And one night, I believe, seven years ago, Mike and Sally were coming back in the wintertime during a rainy night from a dinner they'd been to. And Sally looked out the window and just noticed there's all these newts just like, just, they're like, amazing how many can move across the road. And so she got out, and she noticed that a lot of them had been run over by by a lot of traffic out there, and so she moved them that night. She walked the whole mile of the of the active area, and she was hooked, and she founded the Newt Brigade. And she is she, we call her our brig, or the general of the brigade, and all the volunteers are brigadiers.

Jeff Manson: Very cool. And how did you personally get involved as a brigadier out there?

Richard: I had a mutual friend. My friend Richard Plant and Sally Gale were very good friends, and I heard about it through Richard and couple years ago, well, five years ago, I started going out there. And, you know, I, I say, fell in love with it, but I'm, I love nature. I love being outdoors. And there's just so much to see out there on the road at night. Sometimes it's very crowded and busy with traffic, but other times it's just so peaceful. And it's really neat to be outside at night.

Jeff Manson: I think it's, it's, you know, potentially dangerous, not only for the newts, but for the volunteers as well out there.

Richard: Well, you know, we have a lot of safety equipment. We all look like, you know, your Caltrans or your county workers. We wear orange vests. We have very bright flashlights that we use. We don't always have them at their brightest level. We make that they're very, very bright. And we use them to illuminate the road so that we can see the newts. Because they're, they're the color of dirt, and they're very hard to see. And we have very strict protocols on what our volunteers do when there is traffic. We get off the road, put our flashlight straight down so we don't disturb them. So we've had no injuries to date.

Jeff Manson: And how big is the brigade at this point, and who kind of makes up the team is it mostly neighbors in the neighborhood, other volunteer scientists who all of you drawn to the cause

Richard: All of the above there. I don't know how many are there right now, we have, there's a core group that keep coming back year after year, and then some of the volunteers, they'll spend a year, or less than a year. Most people stick around for a little bit, but then, as they're growing, we get a lot of college age students and young young people, and as they leave to go to college, they're gone. But they, you know, they stay in, they stay plugged in, and they follow us on our Instagram page. We have an Instagram presence.

Jeff Manson: Yeah, we'll put that handle in in the show description as well. If folks are interested in checking that out, make sure that's great. So, so what is it about the Chileno valley that makes it an important habitat for newts? Is it? Is it unique? There are newts getting squished on roads all over the place, and this is just a place where this effort is underway.

Richard: Newts are getting squished on roads all over the place. I am aware of an effort down in Los Gatos, down in the south bay of Santa Clara County, there is a reservoir down there called Lexington reservoir. It's got a dam, so there's water. The newts breed in water, and they hang out the rest of the year up in the hills. So when they cross roads, because us humans have put roads everywhere, they move really slowly, and they get run over and down there that group is they're fighting. It seems like a losing battle. It's hard to get it's hard to get support for them. And basically they they just pick up dead newts. Thankfully, where we are out on Chileno Valley, we've got the Laguna. It's a natural lake, and our population, it fluctuates, but every year we get better at what we do when, in the beginning, we would deal with every newt that we found as we found it, alive or dead. And what we've learned to do is, if a newt is dead, well, it's dead. We can address that because we take pictures of them as well. We can address that tomorrow. So we really focus on the live newts in the evening, because one vehicle can come through, and if the road is covered with newts, one vehicle can, couldn't easily kill 20 or 30. So we we address, you know, we move that live newts and then we address the dead newts. Oh, but I wanted to get back to the numbers in the beginning. I think that of out of the whole number of newts that we would find in an evening, I want to say it was a little more than half were alive. So that means a little less than half were dead. Well, we've since we've gotten better, we're now up to like 70, over 75% are alive. So because we focus on the live ones, we're able to get them off the road before they get squished.

Jeff Manson: Yeah, well, you described the newt migration a little bit just in terms of numbers. But for folks who haven't seen it, can you say a little bit more about what does that look like when they're really out in huge numbers coming across.

Richard: Oh, man, it's, it is insane. You know, when you really it's, I mean, the beauty of being out in nature and focused on an event like this is is that you're you're hyper focused on what you're doing. And when you do that, you see the newts. You see the frogs. There's a lot of Red-legged Frogs out there, there's bull frogs, there's Pacific chorus frogs, but the newts in particular, there's two species of newts out there, the California Newt, which the technical term is Taricha torosa, and then the less plentiful Newt is the Rough-skinned Newt, which is Taricha granulosa. And I don't know what the distribution is, but most of the newts we see out there are California newts, and when they're small, when the juveniles are leaving the lake, they can I've seen them as small as like an inch and a quarter. And the big ones, the big adults, they can get out over eight inches long. And when conditions are right, and that means it's wet, and ideally, it's warm, it's above 55, it's 55 degrees Fahrenheit, or above, they come out by the thousands. And, I mean, you'll see a newt and you'll go to take a picture, and you'll at the corner of your eye, you'll see, like, three more. So you'll deal with the one, you'll deal with two and three, and then you turn around where you've just come from, where there were no newts, and now there's six, and you deal with those six, and you turn back around to go the original and there's six more. It is literally like someone has a bucket of newts, an unlimited supply of newts up on the hillside, and are just pouring newts. It, it's, it's, it's a migration. There's just hundreds one night. A couple years ago, I moved over 1100 juveniles in one night, yeah, by myself. Wow, that was just me. And you know, in an evening I might let me know if I'm getting ahead of myself. Great. You know, we have, we have a group that goes out every night of the week, and each night has one or more road captains, so those are the senior people that know and keep everybody on task and safe. And. And so it just depends on the weather. Some nights you go out there and it's very quiet, you might you might see no newts whatsoever. You might see a handful. You might see 50 or 100 if the rain comes. Sally calls them big nights, she'll send out extra pleas. I often go out there when it's a big night, so I'll go out on any night out there when they need extra help, because when, when the moon aligns and the rain aligns, everything there, there can just be thousands of newts on the road at once, and it's they. They like it. They breathe through their skin. And it seems to me that they really like there's their skin wet, and that facilitates better breathing, because when it's wet, they move fast.

Jeff Manson: So I've heard, and maybe this is urban legend, but that these newts secrete a very toxic substance in their bodies. I've heard of people like the urban legend I heard was somebody had a newt in their coffee pot out camping and it poisoned them or something. Maybe your urban myth. But is there anything to that? Is that part of the newts?

Richard: You know, it's really, it's a good question, Jeff, because these newts, especially the Rough-skinned Newt, the California Newt, have it, but to a lesser degree, they have a toxin in their skin. That's, I believe it's called tetrodotoxin, and it's the same toxin that's in the puffer fish. Oh, wow, and it's super toxic. Now you might say, well, what are you doing out there, moving all these newts across the road? Are you concerned? And so one, you know, we tell everyone, you know, wash your hands, you know, don't handle the newts, and then, like, put your hands in your eyes or in your mouth, and whatever you do, don't eat the newts, because that would be very bad. So, yeah, we it's just something to keep in mind. In seven years, we've had zero problems. I mean just, I mean I handle, during the season, I handle thousands of newts briefly, I pick it up. I walk across two lanes that are one or two lanes of traffic. I set it off on the other side. And I do that for between two and four hours a night, a couple nights a week for a few months. No, you know, at the end of the night, wash your hands, but it's just something so that people know that, like, yeah, these newts have kind of an interesting defense mechanism. Here's another really interesting thing that your listeners might be interested in, so animals have learned don't eat the newts, like, they just figured out, like, otherwise you'll die. Well, you know, who can eat a newt and not die? Is a garter snake, really garter snake. So we find them like on big nights, when the newts are moving in huge numbers, the garter snakes are like at the newt buffet, and you'll see small and large garter snakes out there, like it's just a buffet. But not all of them have the ability to tolerate the toxin. And so what I've heard scientists, we had a scientist Professor come out and give us a talk a couple years ago, and he called it an arms race. And so the newts have poison in them, and some of the snakes can tolerate that poison, and some can't. And so the snakes that eat a highly toxic newt that's too toxic, well, some of those snakes are going to die, and so you're filtering out the snakes that are more sensitive to the poison. Well, guess what? The ones that are that are not so sensitive the poison, there's the ones that are left so they can tolerate it. So the newts are creating a super highly toxic, resistant race of garter snakes, and it goes both ways. So when the snakes eat the newts, the ones that the ones that have the highly toxic, highly high amounts of poison, they don't get eaten quite as much. So the ones that they do eat are the ones that have less toxic poison. So they're filtering out the less toxic newts. And so it's an arms race. They're basically getting more and more toxic newts and more and more resistant garter snakes.

Jeff Manson: We're seeing natural selection in in real time, real, real life.

Richard: It's amazing. It's really amazing. So that's another thing. It's fun to see the snakes out there, because they're beautiful. I forget which species it is, but they're just the coloration is just fascinating.

Jeff Manson: Any, any other interesting aspects about newt, newt biology?,

Richard: Well, you know, I could talk a little bit about just the metamorphosis that they take place when they're in their land based, their bodies look thusly. And then when it's time to go spawn and go into their aquatic phase, their bodies change. And then once they leave the aquatic phase, they shed their skin and they go back to their land. It's, it's, it's kind of cool

Jeff Manson: About how long does a newt live if it gets to live a happy, long life and die of natural causes?

Richard: I've looked online to see this. So like in the wild, they think that it's like maybe 10 to 15 years.

Jeff Manson: Oh, they said they're pretty long lived.

Richard: Although some, some people, say that they could live as long as 30 or 40 years. They don't know that in captivity, they'll last a little longer. They'll last like 20 years. You know, they've got, they don't get run over by cars, and they've got a steady diet. But yeah, these little critters can live that long.

Jeff Manson: Wow. No idea.

Richard: Yeah. yep. It's really amazing.

Jeff Manson: How have local residents responded to the efforts? Are folks generally aware of the migration now and the newt struggles?

Richard: I think, you know after seven years? Yes, you know we've got, we put signs up out there. We put those little like road signs that construction crews put up when they're working. So we let at each end of the road there's about a mile of road, we let you know people know that we're out there. And after seven years, like you know people, people know we're out there. We I don't deal with all the logistics, but I think most nights, someone contacts the sheriff's department and just lets them know, Hey, we're going out, we're going to be on the road. And occasionally a sheriff will come through and just sort of check on us. A couple years ago, we had one Sheriff that came out to check on us, and he just, he was sort of, you know, eyeballing it like he'd never seen anything like this. And then he said he had to go. And then he stuck around for about another half an hour because he started picking up newts himself. It's kind of addicting.

Jeff Manson: I could imagine him would be. Yeah, there's another one here. Yeah, oh yeah, friends out there. If you're just joining us, I'm speaking with Richard James with The Chileno Valley Newt Brigade. We're diving into all things newt and, you know, using this as a way to think about conservation and local efforts around conservation as a whole. It's one of the things I find inspiring about this group and this story is it's so specific. It's this one place, this, you know, one species or two species, excuse me. And and a very concrete task, you know, helping numbers of these folks. If somebody out there is listening and is inspired. How can they get involved with either the brigade in Chileno Valley or maybe help protect amphibians in their own community?

Richard: Well, we've got a website in addition to our Instagram. And our website is www.chilenovalleynewtbrigade.org, so if you point your web browser to that, go to that page, and look at the top, and you'll see a little word that says, “Volunteer”. Click on that. And if you want to volunteer, you can fill out, you know, put your name, rank and serial number, and someone will contact you and invite you out to a training. It's very it's very rigorous because we're very safety conscious, and there's protocols that we want to follow to gather good science. So go to the website and check it out. There's a way that you can donate if you want to. You know, we're sort of self-funded, you know, we use, we consume flashlights and buckets. We have spatulas to scoop up the deal.

Jeff Manson: Actually, that was going to be one of my next questions. Any specialized equipment that you use. What does it look like to transport one of these little guys?

Richard: Well, we, we, you know, we just have five gallon buckets. Are actually not they're too big. We have, like, probably a two gallon bucket. And we have, we bring a penny, we bring a, just a Lincoln penny out there, and put the penny in the photo when we take it for scale. I myself, personally, I move really fast. I move a lot of newts. I don't necessarily follow that protocol. If it's a juvenile newt, I'll put the penny next to it to show that it's a really tiny newt but when it's a big night and there's a lot of newts out there, I don't have time to I don't have time to put the penny and then remember to get the penny. There's a one of our team, Captain, road captains, Christine, who lives in Petaluma, she goes out the next day, and she deals with the dead, and she finds lots of pennies, because in the heat of battle, it's easy to lose your penny. But back to your question. So you know, a bucket, a very powerful flashlight, a phone, ideally with with a waterproof bag on it keep because when we're out there, sometimes it is raining in biblical fashion. It is dumping rain, rain gear, a penny for scale. And then, you know, just an interest.

Jeff Manson: Yeah, an interest and a good set of eyes. Sounds like.

Richard: The little ones are really challenging to see. They blend into the pavement like they're perfectly camouflaged.

Jeff Manson: Yeah, I was curious about the the data piece. Is there any kind of formal data collecting happening, or any, you know, collaborations with scientists or agencies underway?

Richard: You bet, you bet. So what we've, you know, we, we hope to to work ourselves out of a job eventually. It's not that we want to go out there every night in the wintertime to do this, we've been collecting data. And a couple years ago, the group got a grant from the Department of Fish and Wildlife, and that money was allocated to hire scientists. We hired one of the most knowledgeable newt amphibian scientists. Just in California, and she did a study with an engineer. She's the biologist. There was an engineer, and they did a study to try to figure out what is the best way to modify the road out there so that the newts can actually just and other things that the frogs, the Turtles, other animals, can just pass under the road without getting squished. And so our data has gone towards, you know, informing that study. The study is complete. There's been a number of recommendations made. It's still going through the next process. I don't know the exact state where that is, but there's been coordination with the county, with Department of Fish and Wildlife, US Fish and Wildlife Services. And who was the other group? There's, there's an individual. He's Professor up at UC Davis, Gary, I think it's Bucciarelli, and he is involved with us. He looks at our data, and then some of his students, occasionally, we get a lot of students that come down from UC Davis that are real Newt fanatics. And so they come out, and they just, they're in heaven. They're so fascinated to see all these people that care about these newts. And this is what they're researching for their, you know, their PhD.

Jeff Manson: Yeah. And to see, you know, the subject of their research in in situ, in real life, with community members.

Richard: They, they love it. They are so excited. And so they take a lot of photographs, and they're just and they'll come back when they can. They'll come back and help us again and again.

Jeff Manson: Yeah. Well, it sounds like, you know, mentioning these road modifications that could happen seems like a really good step in the right direction in terms of protecting these populations? Are there any other local or state level policies that, you know, in a dream scenario, we could see implemented to better protect these species?

Richard: That's a good question. You know, I don't know. I'm not involved at that level. Your listeners might be aware of a huge wildlife crossing that was put, that was built and is now open down in Southern California. I've seen pictures of that. It's amazing. It is, you know, and in specific, it helps mountain lions who get down as Los Angeles is just sliced up by roads everywhere. And these animals can't breed. They can't, you know, like a mountain lion needs a lot of distance to roam and feed it range. And the 405, and if all those freeways are just death traps, and so that, that wildlife crossing down there is just amazing. And there's, there's a huge one that was put in in Colorado recently, and migrating Elk use it and, you know, build it and they will come, the animals figure it out.

Jeff Manson: Yeah, amazing. Well, you've been working directly with these small, vulnerable creatures for you said, five years now. Has it? Has the experience changed the way you think about nature, or your relationship to nature?

Richard: Oh, It it gets you to slow down. You know, walk in the road. You know, I'll go out there anywhere for two to four or five hours if it's a busy night, and being slowing down and focusing on nature. You know, your ears, you know, we're listening, I'm listening for traffic. So I get out of the road, the Pacific Chorus Frogs. You know, there's, I think, a rough estimate, probably 50 bajillion of them out there. And when they go off, like you cannot hear yourself think, and then whatever causes them occasionally, they stop, and the whole environment just goes silent, and then five seconds later, they turn back on again. And it's being in that environment, you know, a few times and not a year, is just, it's a blessing, I mean, to be out there and really slow down so it, yeah, it's changed me in that I take that in other parts of my life and just try to, like, you know, we're blessed here to live near Tomales Bay, you know, watch the, watch the pelicans flying over, or watch the, you know, it's that time of year when the Canada geese are flying over. We get to hear that beautiful sound overhead. So, yeah, it has, it has changed me, I think in good ways.

Jeff Manson: Any thoughts on newts and resiliency or coexistence? What any, any lessons that the newts have for us.

Richard: Well, you know, they're, they're really cute. They're determined. You know, these newts in their migration, they can, they can travel five or six miles to get to that Laguna. Imagine a little critter that size traveling six. That would be like, I don't know what the Yeah, yeah, the scale, it's huge, many, many miles. It's huge. And they go there, and unfortunately, a lot of them don't even make it across the road now. Now, thankfully, because of your group, in seven years of doing it, a lot more of them have, you know, we, I think we, as humans, need to pay more attention and look at what our activities do to all these species, large and small, because they're all critical in in the habitat.

Jeff Manson: Yeah, well, I mean, that brings me to, I think my last question a good place to wrap things up. You know, some people might listen to this and think of this as a small, local, specific issue. But how would you explain why this matters on a larger ecological scale?

Richard: Every animal on the planet matters. I don't like mosquitoes and I don't like ticks. Those are two that I really don't like, but they all matter. And when we through our activities, whether it's the way we use the land or the way we spray pesticides or herbicides or what have you, and just wholesale take out species in large numbers that has a huge impact on not just that local environment, but there's what's called a “trophic cascade” that you know, goes out like dominoes in both directions. And these newts, they eat a lot of little bugs and worms and snails, and so if there's no newts, well, those animals are going to the ones that they're not eating are going to become a problem.

Jeff Manson: So amount of balance in that, yeah. Well, Richard, really appreciate taking time to come on. KMWR, thanks so much again. And it's, it's getting me inspired to get out there on the road with y'all someday.

Richard: I hope you can, you know, come out, you know, just contact, go to that website. Will do and and we'll walk along the road. And who knows, you might just say, I got to do this again and again.

Jeff Manson: Are there any upcoming projects or community meetings, or any anything folks should know about or, I guess, go to the website.

Richard: The website will be there. You know, we we have potlucks throughout the year. Sally and Mike are such gracious generals of this, of this group. And so we'll go out and have meetings. There's a movie, a short movie was made. And so that's one of the things that new volunteers, watches this movie. And there's, in the springtime, Sally will open up the ranch and have people come out and watch the wild flowers. And then there'll be some newt-centric, you know, some education and bring people up to speed. So it's, it's a lot of fun for people that like nature. Highly recommend it.

Jeff Manson: And again, that's Richard James with The Chileno Valley Newt Brigade. If you want to get more information, you can go to www.chilenovalleynewtbrigade.org/volunteer Is the spot. A lot of great information about newts protecting the rights of passage.

Marin Independant Journal, March 21, 2024

Marin IJ Editorial: Marin’s Newt Brigade continues its wonderful legacy

Aesop is credited with saying, “No act of kindness, no matter how small, is wasted.” When it comes to small, the Greek fablist probably wasn’t referring to newts.

But a number of Marin residents devote time and energy to helping make sure small newts get across the road safely.

It is a deadly dilemma. Local amphibians face the risk of getting smashed by cars as the tiny beings make their migration across Chileno Valley Road to their breeding habitat in Laguna Lake, which is part of the Walker Creek watershed. The salamanders then have to crawl back across two lanes of asphalt back to the woods.

West Marin rancher Sally Gale, after seeing the migrating newts five years ago – thousands of them, many of which had been run over and killed – decided to do something about it.

Sally and Mike Gale search for newts along Chileno Valley Road in West Marin, near Petaluma, Calif. on Wednesday, March 13, 2024. (Alan Dep/Marin Independent Journal)

Since then, Gale’s patrol has grown to more than 80 volunteers who take shifts patrolling a one-mile stretch of Chileno Valley Road, every night from October through March. They pick up the newts and move them safely across the road.

They call themselves the Chileno Valley Newt Brigade and their slogan is: “Protecting rights of passage.”

They have also been collecting data regarding the temperatures and weather.

So far this year, the Newt Brigade has saved around 15,000 newts before they could be victims to the tires of passing cars.

Most of the amphibians they are saving are California newts, listed as threatened species by the International Union of Concerned Scientists, and rough-skinned newts.

They have also helped other species safely across the road – the endangered California red-legged frog, the arboreal salamander, slender salamander and Pacific chorus frogs.

Gale is hoping to convince the county to build possible wildlife bridges – raised roads with culverts – to help ensure safe passage for the amphibians.

Her group has won a $78,000 grant to review possible solutions and the county is amenable to including the work when it repaves the road.

For Gale, not only is she helping life around her, but in the brigade she has met “more good people … who want to do good things.”

Kathy Scott, a volunteer from Petaluma, says the brigade’s work is an inspiration that by working together people can “do things that are big.”

The kindness and care these volunteers show to provide safe passage to those newts is an inspiration that we can make a difference – especially to small newts.

No acts of kindness are “wasted,” whether you are a small, slow-moving newt trying to crawl across what must seem to them like a sea of asphalt or a helpful human showing the ability to care about other living things by giving you a helping hand across a country road.

KPIX | CBS NEWS BAY AREA, March 20, 2024

Marin County volunteer group helping save newt population | The Newt Brigade, Marin County by Brian Hackney

“Taking on a Task in the Middle of the Night” — Brian Hackney reports on the newt brigade in Marin County.

Marin Independant Journal, March 15, 2024

West Marin group acts as crossing guard to protect imperiled amphibian by Krissy Waite

One night five years ago, Sally Gale was on her way home on a warm, rainy night when she noticed a collection of strange, uniform sticks on the ground.

She got out, and, upon inspection, discovered they were newts — thousands of them — including many that had been run over and squished. The Chileno Valley rancher walked the mile-long stretch of road in her heels — her husband following behind her with the car headlights — and saved every newt she could.

“I felt terrible that people were driving over them and killing them,” Gale said. “People were just unaware and they were killing them, so I decided to do something about it.”

Mike Gale, left, and Christyne Davidian look for newts along Chileno Valley Road next to Laguna Lake in West Marin on Wednesday, March 13, 2024. (Alan Dep/Marin Independent Journal)

Gale called a friend at the state Department of Fish and Wildlife, and the Chileno Valley Newt Brigade was born. The nonprofit is a group of about 80 volunteers who walk a one-mile stretch in teams along Chileno Valley Road every night from October through March, which is the newts’ migration season.

The area has two main species of newt: California newts — listed as near threatened by the International Union of Concerned Scientists — and rough skinned newts.

The newts cross the road to get from their woody summer habitat south of the road to their breeding habitat in Laguna Lake on the north side. They then migrate back to the woods across the road in the winter and spring after breeding.

“I had known that the newts move on certain nights, but it hadn’t clicked in me what a slaughter it was for the newts.” Gale said. “At that time I only found five live newts, and about 45 dead ones. By the time I got to the end of that mile I was hard wired to do something about it.”

The volunteers pick up the newts and move them across the road in the direction they were heading. They collect data every night, including the number of dead versus alive, how many are juvenile newts, the temperature and weather, and even how many positive and negative interactions they have with people driving by.

The citizen scientists share this data with the rest of the scientific community via a website and app called iNaturalist. Recently, they have begun collecting the dead newts to give to a herpetologist for research.

This year, the Newt Brigade has saved around 15,000 live newts, and counted 5,000 dead, according to Gale. The volunteers have even noticed more baby newts than in previous years; over 17,000 young newts were counted this season, with 13,000 alive and 4,400 dead. Last season, they counted almost 5,000 baby newts in total.

The group also logs data on other species trying to cross the road — and guards them from cars as they do so — like the endangered California red-legged frog, arboreal salamander, slender salamander, and Pacific chorus frog.

It was pond turtles, however, that brought volunteer Christyne Davidian of Petaluma, to the group. In 2020 the lake dried up. When she was riding her bike around, she noticed turtles emerging by the dozens. She tried to save some and made turtle crossing signs. A neighbor told her about the Newt Brigade.

“I was just getting really upset, like where are the turtles going to go?” Davidian said. “I just felt so bad. I wanted to figure out if I join the Newt Brigade, how can we help the turtles, too.”

Now, Davidian walks the road in the morning, too, to help any of the slower-moving Newts and creatures cross.

“My saying now is that if I can’t save people, I’ll save newts,” Davidian said. “It’s been a huge project for me and I’ve been absolutely obsessed with saving these little creatures.”

Gale said the long-term goal is to get the road altered to allow animals safe passage. This could be in the form of wildlife bridges, raised roads with culverts, and other researched-based solutions. The group has been awarded $78,000 to do a feasibility study on various solutions.

Marin County Public Works Director Rosemarie Gaglione said that the county is considering the newts, and other animals, while designing future projects.

“We are planning to change out culverts when we repave the road to make it easier for the newts to cross,” Gaglione said. “We are open to other ideas and would consider a larger project that makes sense if there is grant funding to help.”

For Gale, the effort is bigger than newts, or even turtles and frogs. It is about awareness and compassion for the natural world around us.

“It’s empathy, maybe, and you know you just realize that animals are in a very tough position right now and people need to do more to respect and support their lives, and they are diminishing all around us,” Gale said. “And the more I do this, the more good people I meet who want to do good things.”

Brigade volunteer Kathy Scott of Petaluma echoed the sentiment, saying that she originally joined the group in search of community. As she spent more nights saving newts, and scraping dead ones off the road, she found a bigger meaning behind their work.

“It was the inspiration of working together to do something that’s bigger than you are,” Scott said. “It supports the idea that people can get together and do things that are big.”

More information about the Newt Brigade, and how to join, can be found at www.chilenovalleynewtbrigade.org.

Point Reyes Light, June 7, 2023

Newt brigade explores safe crossing by Ben Stocking

For four years now, the dedicated volunteers of the Chileno Valley Newt Brigade have been carrying tiny amphibians across Chileno Valley Road to spare them from meeting an untimely demise beneath the tires of cars and trucks. Their efforts have previously won them coverage in the New York Times—and now a $77,876 grant from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife.

The money will be used to seek ways to help the newts safely cross the road without assistance from human beings. The brigade plans to hire a civil engineering firm to consider various options, including lifting a section of the road, altering existing culverts or installing amphibian tunnels beneath the road. United States Geological Service staff will assist in the study, which will be conducted over the next 12 months.

Newts and other amphibians and reptiles are often killed while attempting to reach Laguna Lake in northern Marin County during their four-month spawning season, said Sally Gale, the rancher who founded the brigade.

“Our tiny group is being taken seriously by a government agency tasked with protecting vulnerable species,” Ms. Gale said. “Who knew we would have gotten this far?”

The Marin County Department of Public Works has given its blessing to the study, though any solution that emerges would require the department’s approval and the brigade would need to find additional funding to implement it.

Newts have migrated to Laguna Lake for thousands of years, Ms. Gale said, and if their lives are not cut short, they can live for 30 years. But they must make the dangerous Chileno Valley Road crossing twice a year—once to get to the lake to breed and once to get back to the hillside forest where they live during the rest of the year.

They cross along a one-mile stretch of road, but most of the activity happens along a quarter-mile stretch at the eastern end of the lake. Ms. Gale and her husband, Mike, first came upon the newts while driving home from dinner one rainy night in 2018 and realized that many of them had been crushed.

Ms. Gale founded the brigade to spare more newts from this miserable fate. Since then, more than 80 people have volunteered, many of them retirees. Among them are teachers, a surgeon, a family practice doctor, computer scientists, graphic designers, naturalists, hikers and birders.

Working in teams, the volunteers search the road with flashlights. The newts freeze in the light, and the volunteers pick them up, carry them across the road and set them down in whichever direction they were heading.

So far, the volunteers have logged over 1,700 hours and saved over 7,400 newts.

“On a normal night, we’ll have a team of 10 volunteers with a captain, and they’re out there for about two hours,” Ms. Gale said. “But one night last year, some of the more dedicated volunteers were out there until 3 in the morning.”

For more information, go to www.chilenovalleynewtbrigade.org.

Press Release (May 2023)

Chileno Valley Newt Brigade awarded grant to make Chileno Valley Road safer for newt migration

For immediate release.

For further information, please contact Sally Gale at 707-772-7774

Chileno Valley Newt Brigade awarded grant to make Chileno Valley Road safer for newt migration

The Chileno Valley Newt Brigade has been awarded a grant of $77,876 by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife to study ways to reduce the mortality of newts and other amphibians and reptiles on Chileno Valley Road near Laguna Lake in northern Marin County. The newts are often killed by traffic while crossing the road to reach the lake during their four-month spawning season.

The grant will allow the Newt Brigade to hire Dokken Engineering to study ways to modify the road to allow newts and other animals to survive while migrating to and from Laguna Lake for breeding purposes. United States Geological Survey biologists will assist Dokken in this study.

The Newt Brigade was formed by Chileno Valley ranchers Sally and Mike Gale when they discovered the newts were being run over on rainy nights. Over the past four years, more than 70 people have volunteered to move the newts and other animals off the road on rainy nights. Over 10,000 newts have been rescued in this way, although many are still killed.

The study will be carried out over the next 12 months, and will consider such road modifications as tunnels under the road, raising sections of the road, and other alternatives. Once the study is completed, and an optimal solution is developed, further funding will be sought to implement it. The study is being done in full cooperation with the Marin County Department of Public Works, with the encouragement of Supervisor Dennis Rodoni, who represents the area.

Since implementing a solution to this problem will take at least a few years, volunteers who are interested in helping move the newts on rainy nights are encouraged to sign up at the Newt Brigade website: www.chilenovalleynewtbrigade.org.

North Bay biz, April 26, 2023

Caution: Newt X-ing by Bo Kearns.

Q: Why did the salamander cross the road? A: Because the Chileno Valley Newt Brigade helped them!

In a world where many species are rapidly going extinct, amphibians are at the greatest risk.

Their moist, permeable skin makes them particularly susceptible to drought and toxins. They are an “indicator species,” providing valuable insight into changes in an ecosystem. California newts (Tarichoa torosa) are endemic to the state, yet their numbers are dwindling. Populations in southern California have suffered declines due to loss of habitat and from the introduction of predatory fish, crayfish and bullfrogs, which eat the larvae and eggs. Ponds have been eradicated for development, and streams destroyed by sedimentation resulting from wildfires. In San Diego County, the California newt has gone extinct.

In northwest Marin County, however, they face a particularly unique challenge. … [full article]

KRCB, February 14, 2023

Newts find helping hands in their journey across the road by Noah Abrams

Newts. They’re small, orange, wet and slimy, and they’ve got to dodge a big obstacle. But as KRCB found out, they’ve got some helping hands.

When the rain comes down most of us cozy up inside. But in the Chileno Valley, west of Petaluma - the rain brings one amphibian out in droves: newts.

On rainy nights from December to March, hundreds venture down from the oak studded hills where the mature California and rough-skinned newts live, to their breeding grounds in shallow Laguna Lake.

In their way: Chileno Valley Road. Cutting through rural Marin ranch lands, the road lays an imposing gauntlet right through the newt’s ancestral path … [full article]

State of the Bay | KALW Public Media / 91.7 FM Bay Area, January 30, 2023

Sally Gale’s segment is posted below:

KRON4 News, Bay Area, January 30, 2023

Chileno Valley Newt Brigade is helping a local ‘jewel’ one newt at a time by Miabelle Salzano

PETALUMA, Calif. (KRON) — From mid-November to mid-March, California Newts in Petaluma begin making their way from their terrestrial habitats in the Northern California hills to their aquatic breeding ground.

This year, it seems like the recent rain may have encouraged this migration, leaving volunteers with the Chileno Valley Newt Brigade with their hands full — literally.

“In the past, we’ve never seen more than 250 baby newts; they come out of the lake as soon as it starts to rain,” Gale said. “This year, our wave of migratory babies far exceeded anything we’ve seen before; about four or five thousand baby newts.” … [full article]

The New York Times, January 24, 2023

A ‘Big Night’ for Newts, and for a California Newt Brigade by Annie Roth | Photographs by Ian C. Bates

Salamanders get a little help across the road from some two-legged friends in Northern California.

California is experiencing one of its wettest winters in recent history following a series of atmospheric rivers that hit the state in rapid succession. The recent downpours and deluges wreaked havoc on many parts of Northern California.

But north of San Francisco, the town of Petaluma was spared the worst of the storms. There, the rain has been a boon for newts. The torrential downpours spurred thousands of California and rough-skinned newts to emerge from their burrows and set out in search of a lake, stream, pond or puddle to breed in. And for the first time in many years, the newts have a plethora of water bodies to choose from.

What the newts need now is a safe way to get to their rendezvous points. In many places, busy roads lie between newts and their breeding grounds. In Petaluma and other parts of the San Francisco Bay Area, thousands of newts are killed by cars each year as they try to cross these roads. The carnage in Petaluma is so severe that a group of local residents has taken it upon themselves to stop it.

For the past four years, volunteers have spent their winter nights shepherding newts across a one-mile stretch of Chileno Valley Road, a winding country road in the hills of Petaluma. They call themselves the Chileno Valley Newt Brigade, and their founder, Sally Gale, says they will keep showing up until the newts no longer need them … [full article]

bioGraphic, January 13, 2023

The Newt Normal, bioGraphic, 1-13-2023 | Story by Emily Sohn | Photographs by Anton Sorokin

Droughts, wildfires, floods, and other extreme weather events are putting an unprecedented strain on California newts. With help, scientists think these remarkable animals will be able to persevere.

Anton Sorokin was hiking in the hills near his home in Berkeley California when he came across a pond that was packed full of newts. For a couple of delightful hours, he watched the amphibians swim to the surface for a breath and then plunge underwater again. With a background in herpetology and wildlife photography, Sorokin took some pictures without any particular project in mind. He thought to himself, “Oh, what a great find!”

It was April 2020 and in the ensuing months, Sorokin occasionally drove the 30 minutes from his house to Briones Regional Park, then walked 45 minutes to the pond to see what was happening with the newts. As the season grew warmer, the pond shrank—a typical pattern during the hot, dry summers in this region of California. From his knowledge of the amphibians, Sorokin expected that the water would evaporate eventually and that the newts would strike out for wetter pastures, or else hunker down underground, where some moisture might linger …

Marin Conservation League Newsletter, Jan-Feb 2023

STATUS UPDATE: Chileno Valley Newt Brigade — Protecting Rites (and Rights) of Passage by Kate Powers

Well, it’s that time of year again! Rain has prompted the emergence and mi- gration of bright orange-bellied creatures. Propelled by their side- to-side gait with thick tails and limbs jutting out at right angles from their torsos, their protruding eyes gaze toward their migration destination which lies across Chile- no Valley Road.

These creatures, Taricha torosa or California newts, are a native species. They migrate down from the West Marin hills to Laguna Lake in the Walker Creek Watershed. Salamanders and newts are believed to navigate with the help of small organs in their tiny brains that guide them relative to the Earth’s magnetic field. They also rely on nasal glands in their snouts. Similar to salmon, they smell their way back to their natal ponds ….

Argus-Courier, September 15, 2022

Newt Brigade stands by as winter approaches by Lina Hoshino, Argus-Courier Columnist

When word got out that Chileno Valley Newt Brigade needed more volunteers, Phil Tacata was all in. Phil is a passionate Biology, Marine Science, and Wildlife Museum Management teacher at Petaluma High School who believes in the power of experiential learning for students.

This year, for the first time, he’s adding volunteering with the Newt Brigade as one of the activities his students can participate in…

Madrone Audubon Society Newsletter, September, 2022

Article by Chileno Valley Newt Brigidier Bo Kearns, published in the September 2022 issue of “Madone Leaves, the newsletter of the Madrone Audobon Society.

WIRED, April 2, 2022

How Does a Newt Cross the Road? With Lots of Human Help

Brigades of volunteers are coming to the rescue of thousands of Pacific newts that perish each year as they migrate to their breeding grounds.

The Guardian, March 27, 2022

How does a newt cross the road? The teams trying to end a nightly carnage by Maanvi Singh with photographs by Christie Hemm Klok

Brigades of volunteers are coming to the rescue of thousands of Pacific newts that perish each year as they migrate to their breeding grounds

The Chileno Valley Newt Brigade is a group composed of volunteers with the goal of protecting newts as they cross a busy road that divides their mating grounds from their grassy homes.

Katie Stile documents a newt on the side of the road.

San Francisco Chronicle, March 22, 2022

California highways are creating an extinction crisis. And mountain lions aren’t the only roadkill by Tiffany Yap

… When it comes to saving wildlife habitat and improving ecological connectivity, diminutive California newts — and many other species — need our help just as much as the state’s top feline predators. We are witnessing an extinction crisis on a heartbreaking scale. California, which has the most imperiled biodiversity of the 48 contiguous states, is at the core of that crisis.

The Chileno Valley Newt Brigade is a group composed of volunteers with the goal of protecting newts as they cross a busy road that divides their mating grounds from their grassy homes.

Podcast from Fifth & Mission, San Francisco Chronicle, March 4, 2022

Newts Crossing: A Bay Area Biodiversity Crisis — Newt roadkill is a Bay Area biodiversity crisis

Thousands of the salamanders die on Bay Area roads each year during breeding season. The toll in Los Gatos is one of the largest rates of reported wildlife roadkill deaths in the world. Two volunteer groups are on a mission to stop it. Chronicle reporter Tara Duggan joins host Cecilia Lei to discuss their efforts, and why protecting these delicate creatures is important for the environment.

San Francisco Chronicle, Feb. 21, 2022

“Hello,” Mia Teicher, 16, said affectionately to the newt she found at nightfall in the middle of a two-lane road outside Petaluma. The small amphibian froze and puffed up its orange chest, a warning to potential threats, before Teicher picked it up and carried it to safety.

The Marin high school junior is part of the Chileno Valley Newt Brigade, one of two Bay Area volunteer groups dedicated to preventing Pacific newts from becoming roadkill as they make their way from forest habitat to lakes and streams during breeding season. Thousands of the perilously slow creatures die on Bay Area roads each year, and the volunteers persevere through rain and darkness, even when their efforts are met with indifference, scorn or puffed up chests …”

Sally Gale quickly gets out of her car and removes a newt along Chileno Valley Road at Laguna Lake earlier this month in Marin County. Gale founded the Newt Brigade volunteer group to save the amphibians from becoming road kill.

Santiago Mejia/The Chronicle

This newt was removed from Marin County’s Chileno Valley Road by a volunteer with the Newt Brigade. The volunteers have saved thousands of newts from being run over as they cross the road to breed in Laguna Lake.

Santiago Mejia/The Chronicle

Peggy Bannan (left) and Richard James document and remove a newt along Chileno Valley Road at Laguna Lake.

Santiago Mejia/The Chronicle

This newt was counted and removed from the road by the Chileno Valley Newt Brigade, a volunteer group, that have saved thousands of newts from being run over as they cross the road to-and-from Laguna Lake.

Santiago Mejia/The Chronicle

Bay Nature, January 26, 2022

“On the Road With the North Bay Newt Brigadiers”

“It felt like we were in a locker room, about to burst through the doors, ready to play ball. Sally Gale, head coach, I’d say if I didn’t know better, calls attention in her ranch barn where the Chileno Valley Newt Brigade gathers. Clad in reflective neon vests, counters, buckets and scrapers, the group is preparing for a night full of newt surveys.

The night is nigh. It’s a balmy 54 degrees — 55 is a newt’s ideal temperature — and drizzly. “It just feels newty,” Gale says. She expects it to be a “big night.” On nights like these, volunteers can count 100 newts in a two-hour shift.

Gale inhales sharply and asks, “Now, what do we do if a car comes?”

“We stay four to eight feet off the roadway and point our light downwards,” says Michael Kraus, one of the more experienced of around 30 active and 200 semi-regular volunteers.

At the end of the pep talk, I fully expected them to put their hands together and yell, “Newt glory!” before parting ways. Alas, they did not, but we were in for an exuberant car ride” …

A newt faces the perilous crossing. (Photo by Emily Moskal)

A California newt after surviving the crossing. (Photo by Emily Moskal)

A “Newt Crossing” sign marks the migration area on Chileno Valley Road. (Photo by Emily Moskal)

The Press Democrat, January 13, 2022

Petaluma area volunteers group works to preserve native newt population

On any given chilly winter evening, especially one with rain, you’re likely to find a dedicated group of volunteers in brightly colored vests along a certain byway west of Petaluma.

The group known as the Chileno Valley Newt Brigade considers these cold, damp nights prime conditions for their mission — a quest to save and preserve a local amphibian population.

The Newt Brigade was formed in 2018, after founder Sally Gale was driving home to her ranch along Chileno Valley Road, a rural, 10-mile route that connects west Petaluma to Marin County. She noticed a cluster of nearly four dozen newts making their way across the pavement to their breeding area at the nearby Laguna Lake, on the other side of the hill where from they reside during the dry season.

Gale couldn’t help but be concerned for their safety as their crossings exposed them to oncoming traffic.

“They come out hundreds of them at a time. It’s pretty special,” Gale said. “But you know, they’re pretty vulnerable at that time.” …

Sonoma Magazine, March 2021

Dream Drives: 3 Perfect Day Trips to Experience Spring in Sonoma County, By John Beck

“Further down the road, past MOREDA FAMILY FARMS, you’ll start to see “Newt Crossing” signs just before Laguna Lake appears on the right. The signs are a testament to environmentally conscious locals who banded together as the Chileno Valley Newt Brigade to shepherd low-and-slow-moving California newts safely across the road to breeding grounds in the laguna.”

Photo by John Beck

Photo by John Beck

Marin Conservation League Newsletter, Nov-Dec 2020

MCL November - December 2020, Nature Note Update by Bo Kearns

Every December through February, newts head down from the West Marin hills and attempt to cross Chileno Valley Road to spawn in Laguna Lake. These small, slow moving creatures are vulnerable. Thousands get run over by cars and never make it. Last year they got help. Chileno Valley Newt Brigade (CVNB) volunteers working 2-hour shifts scoured a stretch of the road at night, and often in the rain, for these migrating amphibians. The team collected data to better understand migration patterns and the health of the population and assisted the crossing. Sally Gale, a former MCL director and West Marin rancher, in collaboration with other community leaders, founded CVNB.

Volunteer training

Approximately fifty volunteers of all ages, skills and interests participated in two training sessions. They learned about the newt’s life cycle, how to identify a California newt from other newt species, how to download the iNaturalist smartphone app and how to upload photos to the project site. When confronted with light, newts freeze. Prior to photographing them, a penny is placed alongside for scale. A volunteer then carefully lifts the newt at the midsection and carries it across the road.

Initially, signs and flaggers with wands were posted at each end of the eight tenths of a mile stretch of road being monitored. Volunteers were outfitted with headlamps and flashlights. When passing motorists expressed concerns about the lights and volunteer safety, CVNB adapted. “Our first year was a learning experience,” Sally Gale said. “We realized we didn’t need flaggers, headlamps, or wands. Now when cars approach, volunteers turn off their flashlights, move way off onto the shoulder of road, and wait until the vehicle has passed.”

Data collection and curation

Data related to temperature, wind speed and precipitation was incorporated with other information collected on-site. Triana Anderson, a volunteer and UC Berkeley graduate with skills in data analysis and cartography, curated all the information. This was the first time monitoring the newt population in that area, so no baseline was available for comparison. Data collected and analyzed related solely to those occasions when volunteers happened to be on a particular stretch of the road.

Observations

1,434 newts were observed over the three- month period— 814 Alive, 595 Dead, 10 Injured.

Temperature and precipitation had a direct correlation on crossings. In the absence of precipitation and when temperatures dropped to the low 50s, fewer newts were observed.

The majority of newts crossed in December. Twice as many newts crossed in December than in January, and four times as many than in February.

Crossing concentrations occurred at the eastern end of the observation area in December and shifted to the western end in February.

A high number of juveniles moved away from the lake and across the road into the hills in December. No juveniles were observed in January or February.

Though the number of juveniles recorded is encouraging, more data is needed to accurately determine population ratio.

The high newt mortality rate demonstrates the devastating effect of habitat fragmentation. “It’s indicative of what could be a larger problem,” said Gail Seymour, retired Sr. Environmental Scientist, CA Dept. Fish and Wildlife, and member of CVNB’s steering committee. “Newts are an aquatic indicator species. The health of the population can indicate the health of other aquatic species and, more broadly, the health of a watershed.”

Laguna Lake occupies 200 acres. It’s a natural lake, rare for Marin County and the area in general. In addition to amphibians, migrating and breeding waterfowl, including the whistling swan (Cygnus columbianus) frequent the Laguna Lake watershed.

Amphibians observed

The California newt (Taricha torosa) represented the vast majority of amphibians observed. Their distinctive bright orange belly, protruding eyes and winsome gaze characterize these creatures. They’re a native species having inhabited the region for millions of years. Populations in San Diego County are now extinct. Newts south of the Salinas River in Monterey County are considered a “species of concern” by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. Habitat destruction, road kills and drought are persistent threats to the population.

Over the three month period, other amphibians were seen on the road: the rough skinned newt (Taricha granulosa), California slender salamander (Batrachoseps attenuatus), Ensatina (Ensatina eschscholtzii), arboreal salamander (Aneides lugubris), Northern Pacific tree frog (Pseudacris regilla) and the California red-legged frog (Rana draytonii). The red-legged frog is listed as “threatened” under the Federal Endangered Species Act.

CVNB 2020-2021 season goals

For the upcoming season, CVNB goals are to save more newts and collect more data. Based on experience, collection methodology and use of the iNaturalist app will be refined.

More volunteers are needed! CVNB is also seeking the assistance of a university researcher to help determine population size, and the newt’s role in the Laguna Lake’s watershed biodiversity.

Though the first-year volunteer program was a success, a long term, more permanent solution is needed. CVNB, together with the Turtle Island Restoration Network, is seeking funding for a feasibility study related to road crossing alternatives, particularly those successfully implemented in other areas. Once the options have been determined they will be presented to the community for input.

Want to help save newts?

Want to make a difference?

Visit www.chilenovalleynewtbrigade.org

San Francisco Estuary Magazine, April 16, 2020

A grassroots effort to move migrating newts across a Marin County road has drawn to a close, organizers hope for a more permanent solution by Nate Seltenrich

For roughly half a mile, the two-lane road in a hilly rural area west of Petaluma travels alongside a large, natural body of water called Laguna Lake. On the other side is an oak woodland: the perfect place for California and rough-skinned newts, which spend the dry season in moist terrestrial habitat under leaf litter and wood debris or inside animal burrows. After seeing a number of native newts flattened along the road on rainy winter evenings, a small group of neighbors led by rancher Sally Gale formed the Chileno Valley Newt Brigade. Gale trained some 50 volunteers to monitor the road and physically transport newts across it on a nearly nightly basis throughout the winter migration …

Nocturne | Newt Brigade, March 10, 2020

Newt Brigade | Nocturne Podcast | March 10, 2020 | Hosted by Vanessa Lowe

There's a half mile stretch of road nestled between a lake and a steep hillside in rural Northern California. This road is idyllic and lush, with cows, sheep, birds and abundant wildlife. But if you look closely on rainy winter nights, it's anything but idyllic for the newts and salamanders determined to cross to the other side. Sally Gale is a rancher in Chileno Valley. One night, she resolved to help these tiny creatures, and that's how we got the Newt Brigade.

Press Democrat | January 17, 2020

How to Spot North Bay Newts on the Move, Press Democrat | January 17, 2020 by Jeanne Wirka

Several newt species can be found in Sonoma County, and now is the time to look for them, as they move to seasonal breeding grounds.

Holding a newt is one of the most sought-after wildlife encounters among the North Bay’s elementary school set. Each year, thousands of school kids eagerly await their field trip to one of our regional newt hotspots - Stuart Creek at Bouverie Preserve, the Frog Pond at Spring Lake Regional Park, Ledson Marsh at Trione-Annadel State Park and Martin Griffin Preserve on Bolinas Lagoon, to name a few.

It’s no wonder kids warm to these tiny cold-blooded critters. Unlike other wildlife their size, newts are eminently watchable. They don’t run or fly away, bite, scratch or sting. They don’t slime you with mucus like a banana slug, smear you in musk like a garter snake or pee on you like a toad.

You don’t have to be a kid, however, for a newt to steal your heart.

“Newts are so sweet, and soft and “innocent-looking,” said Sally Gale of Chileno Valley in Marin County …

A California newt (Taricha torosa) clings to a branch underwater in a small stream in Napa County. (Michael Bernard)

California Newt (Taricha torosa) in the San Francisco Bay Area. (Y. HELFMAN)

California Newt, Taricha torosa, amid a pile of oak leaves. (South12photography)

Examining the irises of a newt can help determine which species it is. Rough-skinned and California newts, both found in Sonoma County, have patches of yellow in their irises, but California newts, like this one, have light-colored eyelids. (Jeanne Wirka)

Point Reyes Light, December 4, 2019

Newt brigade acts after rains, December 4, 2019 | by David Briggs

Volunteers with the Chileno Valley Newt Brigade spent their nights this week ferrying newts across a mile-long stretch of road. The team was organized by rancher Sally Gale, who reported finding hundreds of dead California newts crushed by cars last winter. The brigade will meet most nights this winter to walk the road, which follows a lake, with wet gloves, safety vests, buckets and traffic cones.

Point Reyes Light, July 31, 2019

Chileno Valley Brigade Will Ferry Newts This Winter | Point Reyes Light | July 31, 2019 by Braden Cartwright

On a misty night last December in Chileno Valley, Sally Gale and her husband, Mike, were on their way to dinner at a friend’s house when she noticed the newts. They were the same critters she had seen crossing the road for the past 15 years.

“I had this sinking feeling because, I thought, these guys are going to be in trouble,” she said.

On their drive home, Ms. Gale got out of the car and walked the half-mile stretch where the amphibians cross to their breeding lake. She picked up five living newts and 45 dead ones, crushed by the tires of passing vehicles, and carried them to their destination.

“I touched each and every one,” she said. “The mangled bodies. The red, twisted, squashed bodies.”

Afterwards, she said, “That is it. I am going to do something about this.”

Last week, at a meeting at her ranch house, Ms. Gale formed the Chileno Valley newt brigade: a band of volunteer scientists, environmentalists and locals dedicated to making sure California newts can cross Chileno Valley Road safely, from the hills where they live, to Laguna Lake, where they breed.

Present were representatives from Point Blue, the Marin Audubon Society, and the Marin Agricultural Land Trust, and several people with doctorates in scientific fields.

“The least costly and the most doable [solution] is for volunteers to actually move the newts across the road,” said Gail Seymour, a retired environmental scientist for the California Department of Fish and Wildlife.

Ms. Seymour had read about amphibian crossing projects elsewhere before attending Ms. Gale’s gathering. In Oakland, a road in Tilden Park has been closed every winter since 1989 while newts migrate. In New York’s Hudson Valley, hundreds of volunteers have been annually ferrying amphibians across the road for over a decade. And in Cotati, tunnels were built for endangered tiger salamanders that migrate across Stony Point Road to a breeding pond—a project with varied success.

In Chileno Valley, volunteers concluded that manual assistance during the peak crossing season makes the most sense this year, but that more permanent solutions may be possible in the future.

Ms. Gale said that in previous years she observed one large evening crossing in early winter, when the weather was wet but gentle, followed by more sporadic crossings throughout the season.

She hopes that at least 20 volunteers will come to the remote stretch of road when she alerts them of the first major crossing this year. The brigade’s members who have backgrounds in restoration projects plan to tap into those networks for volunteers, too.

Todd Steiner, of the Olema-based Turtle Island Restoration Network, gave a presentation last Monday to the newt brigade on the life cycle of the California newt.

Females lay a few dozen eggs in water that hatch into aquatic larvae. After several months, depending on temperatures, food sources and rainfall, the newts metamorphize and disperse upland. After roughly three years, the newts, now amorous, return to the waters in which they were born to reproduce.

They have few predators, because their skin is toxic, and can live for more than 20 years.

The brigade will focus on the adults crossing the road because the juveniles have a higher mortality rate and don’t necessarily cross as a group. Saving adults that have already lived for three years is likely the best way to maintain a stable population, according to Lisette Arellano, the restoration program manager for One Tam.

Since the brigade doesn’t know exactly when the newts will cross, neighbor James McEwen is planning to set up a weather station so they can predict future migrations. In order to gather data, handlers will also photograph and measure some specimens.

After the discussion at Ms. Gale’s home, the brigade scouted the area where the newts cross to discuss logistics and road safety.

“After the first season we are going to know a lot more,” she said. “So don’t feel bad if we’re not 100 percent successful.” Even if they save just one newt, the effort will be worthwhile.

Volunteers interested in joining the Chileno Valley Newt Brigade can contact Sally Gale at (707) 765.6664 or sallylgale@gmail.com.